It was October of 2016.

Weary and disoriented, Youssef Akhtarini and his wife Reem sat down in the empty room for their initial intake meeting at the main Refugee Resettlement organization, Dorcas International Institute in Providence, Rhode Island where I volunteer. They were from Aleppo, Syria. Aleppo, Syria, was in the news every day and night with horrifying images of destruction and death, and here was a couple who had escaped and been given an opportunity to live in peace and safety, sitting right in front of me.

It was their second day in the United States, after waiting over two years in Turkey. They fled their hometown of Aleppo during the height of the bombing when (they explained to me) bombs from rebel factions would pass overhead in one direction, and the Assad regime’s bombs would pass overhead in the other. Syrians, who prize education, would scurry their children past dead bodies laying in the streets, with the sound of shelling in the distance, to get them to tutors so they wouldn’t get behind in their studies. No running water. No electricity. Then, one of their six children developed a serious vision problem. Fearing for their daughter, and their lives, they fled through falling bombs in the back of a pick-up truck to safety and medical help in Turkey.

During the intake meeting, when Youssef was given the opportunity to ask questions, the first question he asked was, “How can I find a job? I need to support my family.” The second one, “I am a baker, can I bake in my house and sell baklava?” I learned later that he’d brought his large rolling pins all the way from Turkey on his flight to the United States.

I wanted to give them hugs, and to look into their eyes and reassure them, to tell them I was thankful they were here, for their lives, that they were welcomed.

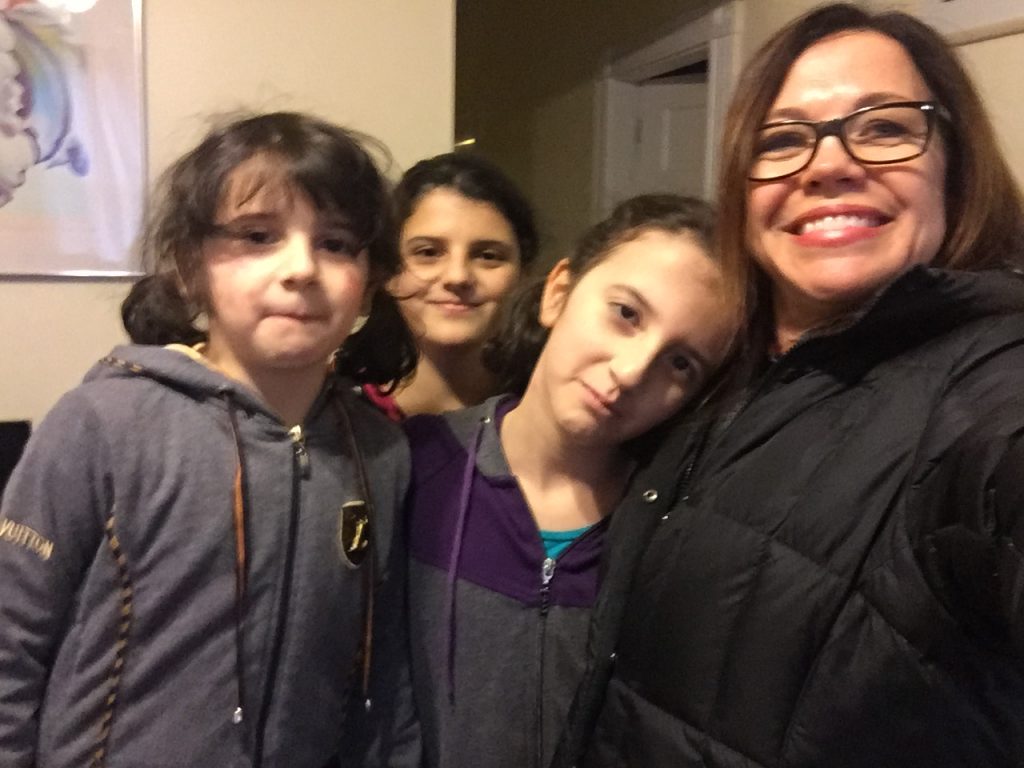

I began stopping by their apartment in the south of Providence.

The first time, I brought a few things I thought they might need as a reason for my visit.

I’d never knowingly met a Muslim family before, nor a Syrian. I didn’t know anything about their culture, or their language, and very little about their faith.

The first thing I learned is that the Syrian people are certainly the most hospitable, kind, warm people on earth. Which, when you are awkwardly trying to get to know someone with few common words, is a blessing. The Akhtarini’s welcomed me into their home, poured me tea, served me dates stuffed with pistachios, and slowly, slowly (‘shway shway’ in Arabic) in time we became friends.

It wasn’t long before I came by the Akhtarini’s apartment for a visit and found Youssef in his tiny kitchen, with flour and cornstarch flying, and his massive rolling pin working phyllo dough. If you’ve never seen phyllo dough rolled by hand, it is a sight to see. What does an artist “who must paint” do? What does a baklava baker who has been creating since the age of 16 do? He bakes — for any occasion, and to hopefully begin to share with Providence, authentic Syrian baklava.

After countless cups of tea, a deepening friendship, and many months; my husband and I began talking about ways to help Youssef realize his dream of creating baklava in Providence, and owning his own bakery. In June, my husband Victor and I closed on an investment property on Ives Street on the east side of Providence.

Will you join us as we help Youssef to realize his dream to create delicious authentic Syrian baklava, support his family and own his own bakery?

We are fundraising for Youssef’s ALEPPO SWEETS START UP:

From ovens to refrigerators, display cases to light fixtures, tables and chairs; from a P.O.S. system to salaries, web design and signage …. funds raised will go towards paying off the interest-free investment loan provided to set up and begin Aleppo Sweets.

GIVE TO: www.gofundme.com/help-youssef-begin-again

Give. Love.

Eat Baklava.

Sandy